Photos by Lars Hasvoll Bakke

As we move between rooms, the cracking of glass underfoot echoes through empty hallways. Sheets of wall paint flap loosely off the walls. Few windows remain intact. Large maps of the former Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact cover the walls of one room. Another few lie strewn across the floor. Moscow barely misses being trampled beneath our boots. Here, in the deserted Krampnitz army barracks near Berlin in the former East Germany, nature is wiping out the remnants of the Cold War. An ever denser forest is making forays into the barracks, hastening the decay of these ruins from two fallen empires.

The last Soviet forces left Krampnitz in November of 1991. The 23 years since seem a small eternity among these gray brick barracks. Several roofs have collapsed. Wrecks of cars and machinery rust here and there. Saplings stretch skywards in some staircases and lofts, reaching for sunlight through roofs which are no longer there.

Despite the decay, numerous treasures remain to be discovered by ruin tourists. Above the entrance to Staff Building K16, a painted red star shines brightly, flanked by hammer, sickle and other communist symbols. The Red Army’s 10th Guards Uralsko-Lvovskaya Tank Division was based here throughout most of the Cold War.

According to local authorities, approximately 6000 soldiers and officers called Krampnitz home in the late 1980s, in addition to 1500 family members and civilian employees. This was merely one of hundreds of such Soviet camps, spread throughout East Germany. At the fall of the Berlin Wall, 25 years ago, Krampnitz housed approximately two percent of Soviet forces in East Germany, which by 1991 still numbered 337 000 men and women. Were the Cold War to turn warm, they would have formed the frontline opposite American and allied forces in West Germany. As the Berlin wall fell, a mere few kilometers east of Krampnitz, the Soviet soldiers remained in their barracks. Only after the formal reunification of Germany did they leave their former East German protectorate.

Founded as a cavalry school in 1937, Krampnitz formed part of Adolf Hitler’s grand re-arming of Germany. It served this purpose until the arrival of Soviet forces in the spring of 1945. They needed accommodation for their vast numbers, which Krampnitz had in abundance. The Red Army moved in, expanded the camp and stayed. Although serving as a Soviet camp for the last 46 years of its life, Krampnitz’ Third Reich origins remain visible. In the main staff building, a grand mosaic depicting the German Imperial Eagle (Reichsadler) over an Iron Cross dominates one hallway. Someone’s attempt at scratching off the Swastika clasped in the eagle’s claws must have been half-hearted, leaving little to the imagination. For whatever reason, Krampnitz’ Soviet heirs left the mosaic in place, perhaps to keep vivid the memory of their beaten foe.

The relics of Europe’s bitter, recent history are plentiful in the surrounding areas as well. Krampnitzsee, the lake outside the camp’s main gate, stretches south-west into another lake, Wannsee. For Berliners, Wannsee is synonymous with bathing, swimming and lakeside leisure away from the city’s oppressive summer heat. For others, “Wannsee” conjures infinitely more sinister memories. At the Wannsee Conference of January 20th, 1942, Nazi officials met to resolve and coordinate the “final solution to the Jewish question” – The Holocaust. Six kilometers south lies Potsdam, a city long known as the site of Sanssouci (“Without Sorrows”), the Rococo wonderland home of Prussia’s King Frederick the Great. As with nearby Wannsee, a 1940s conference would color Potsdam’s name in a darker hue. At the July 1945 Potsdam Conference, Harry Truman, Josef Stalin, Winston Churchill and Clement Atlee decided between them the fate of Germany, Poland and 12–14 million ethnic Germans living throughout eastern Europe. Expelled from their homes, where many had roots stretching back centuries, they became refugees, driven by force into the occupied remnant of what was once a much larger German cultural sphere. Many died on the way. While the victors at Postdam made these decisions together, their distrust of each other was already growing. Potsdam made up another milestone on the path into the Cold War.

As the Cold War turned into a protracted standoff, Soviet forces in East Germany became a permanent presence. When they were not on duty, Soviet soldiers could make use of the camp’s numerous amenities: Four sports fields, two gymnasiums, several cinemas, theaters, bars, mess halls and swimming pools, as well as water sport areas on Krampnitzsee and an officer’s casino.

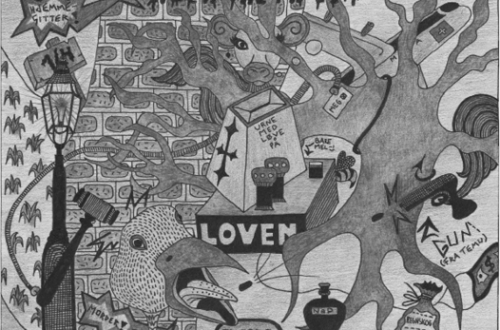

A Kindergarten for the officers’ children also lay within the camp. Its colorful, evocative murals have kept well, but give off a ghostly impression amid the silence of these decaying surroundings. In one indoor Basketball court, the broken wood floor pokes out at sharp angles, reminiscent of a stormy sea. In the grand gymnasium, large murals once proclaimed the friendship of communist peoples, setting the stage for noble, athletic competitions between East Germans, Russian and other nationalities of the eastern bloc. Only slivers of these murals remain intact. They won’t last much longer.

Foreign footsteps and voices in the hallways bring us to a tense halt. The distorted echoes remind us of Russian. If there’s anywhere we might develop a fear of ghosts, it’s here. A group of four young Poles soon appear at the end of a corridor, all armed with expensive cameras. We greet, exchange tips in English on interesting buildings and relics we have found, and part ways. In the few hours we spend in Krampnitz, we meet a dozen other visitors like them. Here, as in Berlin just to the east, the time for such Cold War ruin tourism is quickly running out. While it remains to be seen who will deliver Krampnitz its Coup de grâce, the official plans have been ready for years. Berlin’s rapidly growing population needs housing. If the plans come to fruition, 4000 people may soon live in peaceful, idyllic surroundings at the lakeshore of Krampnitzsee, with the innumerable thrills of Berlin a short distance away.

While the camp’s newest buildings are to be replaced, its oldest buildings – the Nazi barracks – have been deemed by law to be worthy of preservation, and are to be renovated. However, local authorities have argued amongst themselves for years on how all this is to be done, and by whom. An alliance of wind, rain and trees meanwhile work steadfastly to lay waste to Krampnitz and return it to nature. Many of the Soviet-era garages have already capitulated. The solidly built Third Reich barracks take longer to defeat. There, nature has penetrated no further than the lofts.