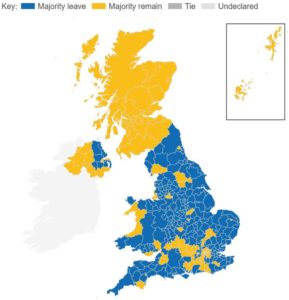

On June 23rd 2016, the UK voted 51.9% to 48.9% to leave the European Union, creating an unprecedented situation. The tension of the result was ubiquitous, with major discontent felt by Scotland most of all. All 32 council areas within Scotland backed remain, averaging 62% to 38%. Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon described it as “democratically unacceptable” that Scotland should be pulled out of the EU against its will. Following the rhetoric of the Brexit and remain campaigns, it is safe to say that the result is interesting, if not unexpected, especially for the people of Scotland who were naively optimistic due to their ignorance towards the views of England. The nation’s cluelessness is anticlimactic, with everyone thinking they knew what would follow a “leave” vote but now everyone realising that the consequences of this unparalleled scenario were speculation more than anything else.

Where do we go from here?

Can the UK benefit at all from ongoing relations with the EU? Can Scotland’s polemic against the leave vote be assuaged at all, or are Scotland and Northern Ireland, which also voted remain, doomed to follow the wishes of the other parties to the UK? Despite the polarisation of pro-remain and pro-exit views, it may be possible for a compromise to be reached – the divorce of this 43-year marriage need not be inimical and hostile.

A Norwegian model?

The UK could adopt the Norwegian model, whereby they could leave the EU but still remain part of the European Economic Area (EEA) as a European Free Trade Association (EFTA) member and, thus, the single market. This frees Britain of the chains of a political union and Brussels bureaucracy whilst retaining the advantage of trade with EU member states and other countries around the world. Whilst not being restricted by all EU policies, the UK’s sovereignty will still be mitigated to an extent (albeit a lesser extent than when in the EU) as they would have to adhere to EU rules relating to, among others, the internal market. On the flip side, the UK would have to fork out money to fund EU projects whilst having no influence on the outcome of these projects – as former UK Prime Minister David Cameron said “while they pay, they don’t have a say”.

This model has the potential to quell nationalist uneasiness for Scotland; a nationalism like no other. A nationalism that aspires to secede from the UK, where it has gained many devolved powers, but that also wants to associate with an undemocratic, top-heavy union of 27 other member states. A nationalism that doesn’t seem to desire the power to rule free from external impediments, but that stems from identity and patriotism. The Norwegian Prime Minister, Erna Solberg, does not think that this model would work for the UK. She opines that Norway was part of many European bodies but they did not have a say on the issues that were most important for the Norwegian people, including farming and fishery policies. Now being part of the EEA, Norway are exempt from EU agricultural and fishery policies. Solberg does not think that these are the issues that Britons prioritise, so becoming a member of the EEA may not be of any benefit. She doesn’t think that Britain will be able to cope with not having a say in Brussels.

A Turkish model?

Another option for the UK is the Turkey model. Turkey is part of a Customs Union with the EU and not part of the EFTA or EEA. Due to this, they have partial access to the internal market and, as such, are not subject to quotas on certain exported goods within the EU and they don’t have to burden tariffs when exporting and importing goods. Unfortunately, these bilateral treaties only extend to goods, not to services. Turkey are required to implement policy similar to EU policy in areas where they are part of the single market.

If Britain were to adopt this model, then they would lose sovereignty over trade as they would not have any say over the EU rules that would have to be followed. This is unlikely to be the best option for the UK as Turkey’s relationship with the EU is founded very much upon their aspiration to eventually accede as an EU member state. Turkey benefits due to the advantages that the agreements have over goods, but this would be unlikely to benefit the UK as much because they’re more dependent on agriculture and exporting services than Turkey is.

“Hard” Brexit

A clean break altogether is a possibility. This is based on the WTO-only model, by which the World Trade Organisation set a minimum threshold of rules for international trade. These rules are free from constraint from EU laws and free from financial contribution or free movement of persons. This is the default model i.e. the one that will be applied if no other agreement is reached. This model would put the UK at a big disadvantage for trade relations as they would be treated a lot less favourably in the single market and they would have to pay a higher tariff in order to be able to trade with EU countries. The WTO are very limited with what they offer, obviously just matters regarding trade. They do not cover matters relating to foreign policy or counter-terrorism. This would be the model that would allow the UK the most autonomy and sovereignty, but there is likely to be some assuagement of sovereignty through diplomatic relations.

A Scottish sortie?

Whether or not Scotland remain in the Union or not is yet to be seen. Being a Scot myself, I do identify with the very niche take on nationalism – Scottish first of all and British second, if at all. I feel that a “hard Brexit”, i.e. cutting all ties with the EU, would make Scottish independence a little less desirable as it would create a hard border between Scotland and England. Whilst this may seem perfect for some extremely patriotic Scots, I think it would generate too many obstacles for trade and migration. The Scottish secretary, David Mundell, said that Scotland «trades over four times more with the rest of the UK than with the EU» so it is very unlikely that Scotland would want to jeopardise their relationship with England. Nicola Sturgeon has said that she will only call for a second independence referendum if it is the only way that Scotland can continue relations with Europe.

History’s most complex divorce

Possibly going down as history’s most complex divorce, it is difficult, if not impossible, to determine the full array of consequences that Brexit will have on the UK. I think it is likely that the UK will adopt a “soft Brexit” and a variant of the Norway model, paying millions of pounds to have access to the EU single market, but nothing like the £9bn it currently contributes. This could overcome much of the Euroscepticism in England and subdue the xenophobic undertones of the Brexit rhetoric as the UK would regain control over their borders.

Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union governs secession from the EU. This process will apparently be invoked in 2017 by UK Prime Minister Theresa May, and will take two years to become effective; two years of uncertainty for Britain while they frantically try to adopt a model that is suitable for them, or maybe even make their own model that will encourage other EU member states to follow suit. All we know right now is that, well, we don’t know anything really…

![]()

Caitlin Alexander is an undergraduate Law student at the University of Glasgow and is studying for a year at the University of Oslo. She hopes to pursue a career in human rights.