Our species designation today is not best described as “posthuman”. No, “we are compost”: The remains are ready to grow new life, with the aid of other species.

Skrevet av Amici Nybråten

The Chthulucene: A Post-Apocalyptic Condition

The apocalypse, you say? It already happened. Many times, and by our hands.

Living in a small, western, affluent, and largely safe society, it might not seem like it. But it happened. It happened to the indigenous peoples of the Americas when Westerners arrived with gunpowder, disease, and forced Westernization. It happened more recently, and at incredible speeds in the industrially efficient extermination camps of the Nazis. Later today as I write, it happens to the people of Gaza, their homes obliterated by fires from the sky, while the dead amass faster than proper burials can be made, and the living go hungry with broken bodies and traumas for new generations.

It doesn’t happen to us, not in our cozy homes. Yet, this apocalypse, where hasn’t it happened?

Forests cut down. Species wiped out. Biomes irradiated by atomic testings and leakages. Mountains blown apart for minerals. Waters polluted. The oceans full of microplastic. In that last example, not even we, in our cozy homes, are safe from the apocalypse as we luxuriously digest our Atlantic salmon. Here, not even our concrete walls, or our trusted armies of border guards, can keep us safe and shielded from a world burning with the fires of climate change, war, and industrial madness.

The apocalypse is not a future yet to come. It has already come, already happened, and is already happening. This is the background for the 2016 book Staying With The Trouble: Making Kin in The Chthulucene, written by Donna Haraway. Despite its dismal background, this book is not a story of loss, but a mental toolbox for not so much hope or optimism, as defiantly working for the survival, and eventual thriving, of one’s social- and ecological environments. Of staying with the trouble.

The apocalypse has already happened. The question is not how to prevent it, not really. The real question is how to live with what has happened, and deal with what is happening. Not to shy away from our responsibilities for the world no matter how fucked it is, but to embrace that responsibility, in the sort of mature manner that only an individual intimately connected to their own living world can do.

Chthulucene – this term has several meanings to Donna Haraway. But initially, she describes it as:

“a kind of timeplace for learning to stay with the trouble of living and dying in response-ability on a damaged earth”

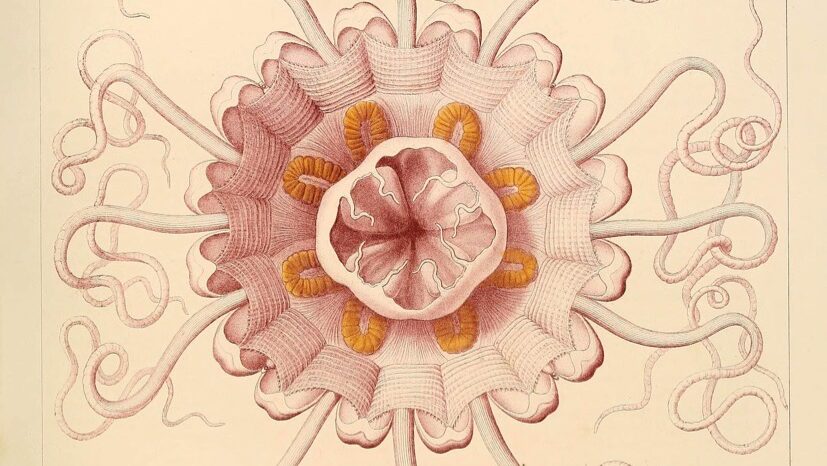

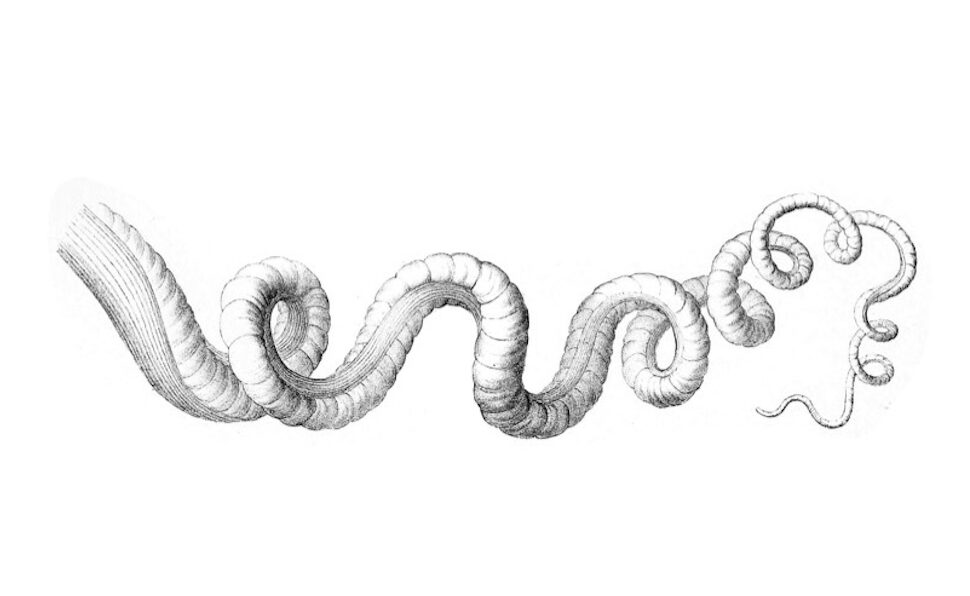

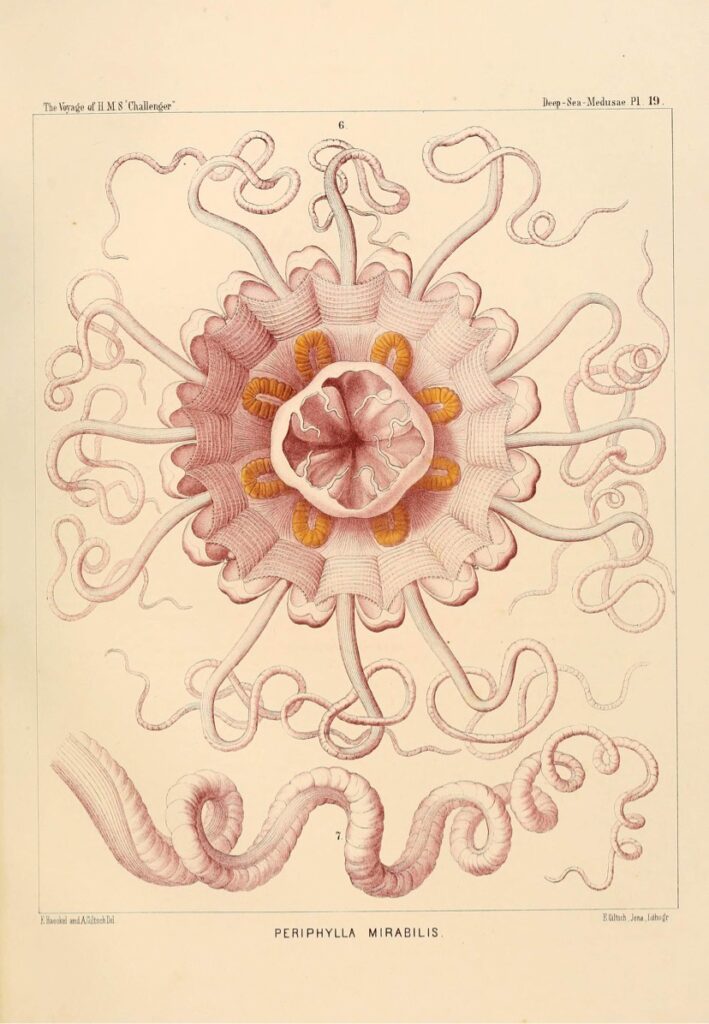

Please read that a few times. With this idea in mind, I would like to argue for one idea that is useful, maybe even necessary, in this toolbox of hers. I’d like to talk to you about tentacles. Though first, I’ll have to provide you the conceptual runway.

Probing Tentacles

Haraway’s intellectual fame came particularly from her decades-old essay A Cyborg Manifesto, in which she tackles the effects of technology on gender, and suggests that technology will lead to “the profusion of spaces and identities and the permeability of boundaries in the personal body and in the body politics.” In other words, Haraway suggests that technology erodes and frees us from distinct genders, because the combination of technology and people (i.e. smartphones in our time) make us more like “signals, electromagnetic waves” which are “fluid”, as opposed to our mere given physical form, which is “material and opaque”. Considering the ubiquitous roles played today by internet anonymity, combined with identity-exploring avatars in social media and games, I think many would agree when I say that her pre-internet assessments were utterly prophetic.

A few decades later, in Staying With The Trouble, Haraway’s profusion of “spaces and identities” from the Manifesto is extended to a “multispecies flourishing on earth, including human and other-than-human beings in kinship.” The word kinship is a central theme in her book. Haraway is quietly criticizing our “human exceptionalism”, our “comic faith in technofixes”, which foresees a supreme human species more capable than any other at solving issues. A governing master species of the world, organizing every other species into submissive places, fulfilling optimized functional roles in grand, magnificent human designs.

But – we are the problem, we are the issue.

To Haraway, the solution must then be clear: we need other species, not as disposable slave labor, but as allies. We need them as kin (or “odd-kin”), with whom we conduct sympoieses – a “making-with”; a “becoming-with”; a partnership, for “partial recuperation and getting on together”, in this very fucked up world.

Tentacular thinking, the subject of a whole chapter in this book, is a form of being in which we humans, much like the curious tentacle, probe for possibilities of making kin, of joining with other species in sympoiesis. I see her idea as a form of sensitivity to interspecies possibilities for collaboration. A post-Nietzschean and Radagast-ian new definition for the Übermensch. As Haraway says, our species designation today is not best described as “posthuman”. No, “we are compost”: The remains ready to grow new life, with the aid of other species. And owning that fact about ourselves, we become more capable beings. More capable of imagining times and places for “unexpected collaborations and combinations in hot compost piles.”

Tentacular Morality

To make ourselves into moral beings, we need first to make ourselves capable of practicing moral acts. We need the moral virus.

Haraway believes, as she shows us in the chapter “Awash in Urine”, that exploring our interconnected lives or exploring avenues for new connections, leads us to become infected with a virus of “response-ability” – the ability to respond to injustices across territories, generations, and species. That is to say, we become aware of how our actions and relations affect or may affect others in the world, including the distribution in space and time of suffering and death. Too much suffering, too much death, and we create an unjust world. A world of disabled beings, and where human ethnicities or whole species of animals ceases to be.

Haraway calls the result of this exploration “cultivating response-ability”, and the act itself requires tentacular thinking: probing possibilities with sensitive appendages of awareness and thought. It requires us to think across traditional boundaries of kin, to make new and odd kinships: across peoples, across species. Together, collaboratively, we make our world better, healthier, more capable of sustaining itself. A place of thriving.

That is why I say: Morality Needs Tentacles! Because to make ourselves into moral beings, we need first to make ourselves capable of practicing moral acts. We need the moral virus. We need it to grow morally, to mature – every one of us. And to get it, we must expose our minds and bodies to a world of differentiated life, with different needs for surviving and thriving, and with different capacities to add to the work of sympoiesis. In other words, we need, as Haraway suggests, and invoking Hannah Arendt, to involve ourselves with others – but respectfully. Not as an invasion of other creatures’ spaces or projects, but as inviting others to converse, collaborate, coplay. We must be curious about their worlds, how they already are involved with it, and what it is that they care about and offer for our involvement. As Haraway insists:

“It matters what thoughts think thoughts. It matters what knowledges know knowledges. It matters what relations relate relations. It matters what worlds world worlds. It matters what stories tell stories.”

Unpacking parts of this, we can say that if we, unilaterally, set ourselves the tasks of thinking something, knowing something, or building a relation to something, we risk reproducing our own abundant faults into our thinking, knowing, and relating. Therefore, we need others, something different from ourselves – we need sympoiesis. And to get there, we must start by growing tentacles: curiously and sensitively exploring the surprising possibilities, for living, for thriving, and getting on together.

Further reading

Donna J. Haraway. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century”. In Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, 149-181. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Donna J. Haraway. Staying with the Trouble : Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Experimental Futures: Technological Lives, Scientific Arts, Anthropological Voices. Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2016.

Amici Nybråten, født 1992, har en bachelor i filosofi fra UiB og går biovitenskap ved UiO