Oh, Valentines day. Pure bliss for one, the worst day of the year for others. Everyone knows that losing your love hurts. Argument asks the crucial question: Can you die from a broken heart?

The Story of a Broken Heart

[highlight]By Jannikken Bømvik[/highlight]

This article was published in Argument #1 2014. A Norwegian version can be read on Aftenposten Viten.

These stories, you have all heard them, even seen them in the news. Typically it’s the old lady who died just a few days after her beloved husband, her heart being so overwhelmed with grief it just stopped beating. And you’ve probably thought that it is sad and romantic, and the more skeptic part of you thought «that is sad and romantic but it is also a load of crap». Some of you have also heard, or said the barely comforting post-break up words; «you will get over this». But what if you don’t? Can the end of a relationship or the loss of a loved one kill you? Can you die from a broken heart?

Is it true?

The answer is yes, although the medical community would probably appreciate some modifications to this statement. Regardless of whether you believe in everlasting love and soul mates or have a more scientific approach to your love life; grieving the loss of a loved one can in fact destroy your heart. It doesn’t actually break, a least not in the most literal sense. However, its function decreases and leaves the person – usually a woman – suffering with symptoms that can make her and her doctor suspicious of a heart attack. It also resembles a heart attack on the typical tests ran at the hospital when a person comes in with such symptoms. But on a closer look a small percent of those will be diagnosed with the so called «broken heart syndrome».

Love hurts

While broken heart syndrome sounds a little bit like a Taylor Swift song, the disease was originally known as Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC). It got its name from Japan, Takotsubo being the word for the trap used to capture octopuses, describing what the left ventricle of the heart looks like in this condition. In English we would usually describe it as «boot-shaped», or «balloon-dilated». Throughout the years the disease has been known by many names, including transient apical ballooning syndrome, apical ballooning cardiomyopathy, Gebrochenes-Herz-Syndrom, and stress-induced cardiomyopathy. [pullquote]Things like losing lots of money, speaking in front of an audience or even something as random as a surprise party (!) may give you a ride in the ambulance to the nearest hospital[/pullquote] The latter may be the most accurate when trying to explain what actually happens. Cardiomyopathy means dysfunction of the cardiac muscle cells, and TTC tends to occur during an especially emotionally stressful time. TTC was first reported in Japan in 1991, but it has also been recognized more recently in the United States and Western Europe.

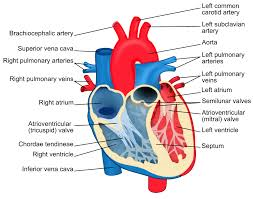

[accordion] [acc title=»The facts: Normal function of the heart»]

- The heart functions as two separate pumps; the right side pumping blood through the lungs, and the left pumping blood into the rest of the body.

- Each of the sides is a two-chamber pump consisting of one atrium, and one ventricle.

- The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the body via the veins, and pumps it into the lungs via the right ventricle and pulmonary artery.

- The left atrium receives blood that has been oxygenated in the lungs, the blood then travels via the left ventricle through the aorta to peripheral arteries.

- Four main valves of the heart opens and closes due to pressure differences in the chambers to maintain this two circulations; the pulmonary and the systemic circulation

- The heart is contracting and relaxing due to an automatic rhythmical electrical discharge originating in the sinus node in the right atrium. [/acc] [/accordion]

Mysterious ways

Despite how strange it might sound, TTC is a well recognized disease, with an actual scientific explanation. There are some uncertainties about the exact process of this syndrome, but we know something; in TTC the cardiac function deteriorates, due to a pathological dilation of the left heart chamber. This dilation makes it harder for the heart to pump enough blood into your aorta, leaving your body with less oxygenated blood that it’s in need for. The rest of the heart is trying to make up for this by keeping up a normal and often increased force of contraction. People affected with TTC typically show symptoms of chest pain, a subjective feeling of difficulty breathing medicinally called dyspnea. Other symptoms can be irregular heartbeat and a feeling of general weakness.

The exact reason why the heart dilates in this specific way remains unclear, but a sudden surge of stress hormones like adrenaline has been proposed as one explanation. Another one is that the vessels supplying blood to the heart temporarily constricts, limiting the flow of oxygen. Several other mechanisms have also been proposed but a definite conclusion has yet to be proved.

Only love can break your heart?

Well, not exactly. The broken heart syndrome doesn’t necessary occur in the event of lost love, although this is what it has earned its fame for. According to the well-known Mayo Clinic in the USA, also medical issues like an asthmatic attach, an infection or major surgery can lead to TTC. Also things like losing lots of money, speaking in front of an audience or even something as random as a surprise party (!) may give you a ride in the ambulance to the nearest hospital.

The heart will go on

TTC is not a very common disease. Studies have reported that 1.7-2.2% of patients who had suspected acute coronary syndrome, which is due to blockage of blood flow to the heart, was subsequently diagnosed with TTC. Luckily, most people will survive TTC, and have a complete recovery within weeks or months. Bed rest and typical heart medications which reduces the workload on the heart are effective.

Regardless of your belief in love – or in science – chances are your broken heart will mend again.

About the author: Jannikken Bømvik (f.1988) studied social anthropology at Norwegian University of Technology and Science, bachelor of nutrition at Atlantis Medical College in Spain and Norway and is now studying medicine at Medical University of Lodz, in Poland.