Tekst: Sverre Tidemand

An Unconventional Art Form

I’m a fan of cartoons. Growing up, I fed my imagination with a steady diet of the stuff, and to this day I still do. I like the stories, I like the plethora of art styles and character designs, and I like how it can kindle such enthusiasm among fellow devotees.

As a concept, animation is an extremely commercial art form. In 2020, the 3D animation industry had an estimated worth of over $17 billion. The medium is dominated by titans such as Walt Disney Animation and Warner Brothers, which put millions of dollars into their projects: Disney’s Frozen 2, for instance, had a budget of over $150 000 000. With their vast financial and publicity resources, these companies can dictate the industry standard in terms of stories, characters, and art styles.

However, these juggernauts can be challenged, and among industry rebels the name Ralph Bakshi resonates. His cartoons, with their hard-line drawing, multi-media cinematography, and unapologetic depiction of adult themes, made him famous – and infamous – throughout the 1970s and 1980s. But not only did his movies rebel against the Disney establishment, they did so while doing well at the box office. So, who was Ralph Bakshi and how did he become the so-called «Bad Boy of animation»?

The «Bad Boy of Animation»

The three films which form Bakshi’s early career as a filmmaker – Fritz the Cat, Heavy Traffic and Coonskin – are stories of urban decay, presented in what can only be described as animated collages.

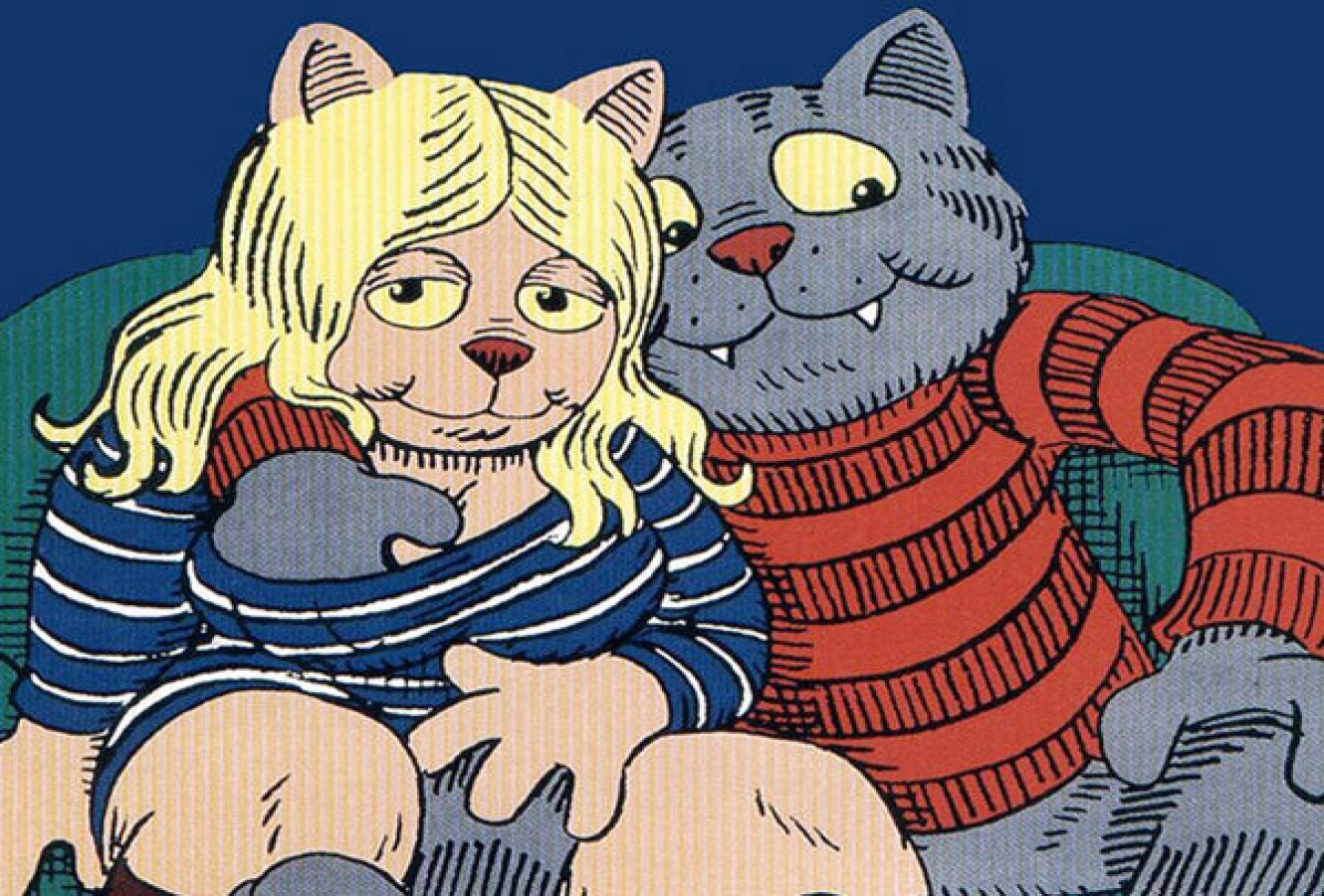

Fritz the Cat (1972) follows the titular feline Fritz, a college student bored with academia who sets out to live life to the fullest. This leads to a three-part adventure involving bathtub orgies with college girls, a trip through Harlem ending in Fritz starting a race riot, and hanging out with sadistic, drug-addled, neo-Nazis.

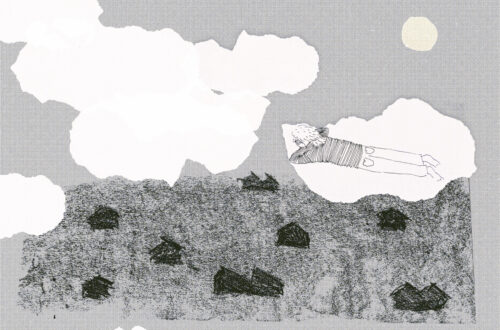

Heavy Traffic (1973) is about Michael Corleon, a fledgling cartoonist, and his meanderings through his rough-and-tumble Brooklyn neighbourhood populated with lascivious photographers, dim street-hoodlums, legless bouncers, aggressive hookers, nymphomaniac transvestites and demonic mobsters.

Coonskin (1974) tells the story of Brother Rabbit, Brother Bear and Preacher Fox, and their escapades in Harlem, framed as a tale told in live-action by an aged Black prison escapee while waiting for the getaway car. Here, armed with their wits and no shortage of muscle and firepower, the three go toe-to-toe against false prophets, racist cops and decadent mafiosos in a quest to help their Black peers.

All three films had, by industry-standards, shoe-string budgets: Fritz had $700 000, Traffic $950 000, and Coonskin $1.6 million. These were low compared to Disney’s Robin Hood (1973), which had a $5 million-budget, and The Rescuers (1977) which had a budget of $7.5 million. However, Bakshi and his teams found ways around their budgets. One method was to skip pencil-tests, a process in which animators digitally capture rough pencil drawings to check how their animation is moving. To save time and money, Bakshi would flip through the animators’ drawings, timing them by hand before applying them to animation-cells. For someone like Bakshi, tight budgets left room for more creativity.

For backgrounds, Bakshi and his friend Johnnie Vito would wander about New York, photographing streets and buildings which they would incorporate into the cartoons’ backgrounds. While working on Fritz, these were painted with watercolours, but in the subsequent pictures they resorted to simple filters. In other instances, they used original archive footage, such as the vaudeville performance in the bar in Traffic or the steel mill in Coonskin. The cartoon characters would then be superimposed on these non-animated backgrounds. Bakshi even implemented the sounds and voices of the streets into his cartoons. Throughout all three films, Baskhi – armed with a Nagra tape recorder – recorded conversations with construction workers, barmen, family members and even recorded street ambience. All of this would then be incorporated into the film. Most of these recordings range from grainy to downright inaudible, but nonetheless add to the sense of urban grit and decay that ooze through the films.

Finally, there was the music. Baskshi, who had become enamoured with Jazz after finding a discarded Art Blakely album in his youth, incorporated various songs into his first three films, such as Bo Diddley, Billy Holliday’s Yesterday, and Take Five (which Bakshi called his «good-luck song»). According to Bakshi, the rights to these songs could be purchased for as little as $50-100 a piece.

When Cartoons aren’t just for kids

While retired from the animation scene, Bakshi is quite optimistic about the medium’s future: «[…] [A]s more animators are laid off and the art becomes repetitive, there is going to be a lot of angry guys going solo». So, while he believes the medium is in a slump, this is only temporary. In fact, the bounce-back can be seen online where various independent animators show a wide array of skills and techniques that go against the big-budget conventions. There’s Harry Partridge, whose many cartoon shorts and ongoing Starbarians series use clean lines with a combination of nerdy and bawdy humour; Max «Hotdiggedydemon» Gilardi, creator of witty and spectacularly drawn shows like Brain Dump; Cas Van De Pol, who makes cartoon reviews of various animated films and games, deploying a child-like, yet incredibly expressive style that sets his channel apart. And then there’s Vivienne «Vivziepop» Medrano, whose team are currently working on an animated musical set in hell: Hazbin Hotel. What these animators, and many more besides, have in common is that they are pushing the boundaries of animation. It doesn’t have to be clean, reverential or (in some cases) child-friendly – showing the various ways it can entertain the public, which in turn fund their projects. So, while Bakshi is no longer in the director’s chair, his films proved the simple but lasting truth: That cartoons do not have to be just for kids.

Om forfatter: