Tekst: Mila Apostolova

Illustrasjon: Mette M. Kaljas

It is common to perceive the transition to adulthood as gender neutral. However, becoming a man is very different from becoming a woman. To highlight these differences, I will focus on the rites of traditional societies and communities for girls and boys, to observe the symbols and patterns in such rituals.

Before I begin, what does it mean to become an adult? From a biological perspective, an adult would be someone who has reached sexual maturity. In a more human context, the term adult is linked to social and legal concepts such as maturity and autonomy. Since it is a notion anchored in the social sphere, different cultures have events representing the transition from childhood to adulthood, called rites of passage. They can refer to religious ceremonies such as the bar mitzvah, but also to much more banal situations such as the first cigarette smoked.

Coming from the Latin word “passus”, the term passage designates the act of moving. It represents a march towards elsewhere, a journey, an ongoing transformation process. A rite of passage is a ceremony that takes place when an individual leaves one group to enter another, in this case it would be moving from the social group of a child or adolescent to the status of an adult. The rites imply a significant change in status in society and giving roles to individuals.

From boy to man

Waumat

In the Pará region in Brazil, the Sateré-Mawé people have practiced the Waumat ritual for centuries. Preparations begin when a small group goes to the forest to collect tucandeira ants, known for their extremely painful bite, compared to the pain of being shot. After finding their nest, the group carefully collects hundreds of ants and takes them back to the village. There, they are placed in a bucket of water with chopped cashew leaves. This mixture is used to anesthetize the insects so they can be handled and fixed inside a pair of handmade gloves.

The ritual officially begins when the young boys put their hands in the gloves, while the ants are awakening. Scared and trapped, they start biting the boys’ hands. This process is also accompanied by people dancing and singing, helping the young boys ease the pain by focusing on the rhythm and external stimuli. Many Satéré men explain that this ritual brings some sort of satisfaction and fulfillment, since overcoming such physical pain creates a deep feeling of pride. After their first experience with the ants, the Satéré are considered men, but they are still expected to go through the rite 20 times in their lifetime.

Fulani

The Fulani people are one of the largest communities in West Africa, known for their painful rites of passage related to adulthood. First, a group of men gather to search for a perfect stick. After finding one, the stick is sharpened and used as a key element throughout this rite of passage. The boys have an opponent each, and their objective is to whip their opponent with the stick as hard and as much as possible, while appearing to endure the beatings they receive.

Only one of the two fighters can pass the ritual, bringing a strong sense of competition. The boy who loses the fight also becomes an adult, but enters a lower status within adulthood. The ritual embodies both courage and shame, since the losing boy is perceived as too weak and unfit to be called a real man. Becoming a man not only comes from the victory, or the endurance of pain, but also with the transformation of one’s body after undergoing such fights. The scars on the boys backs and ribs are the visual mark of someone who left childhood and has entered a new status: the one of an adult.

Sepik

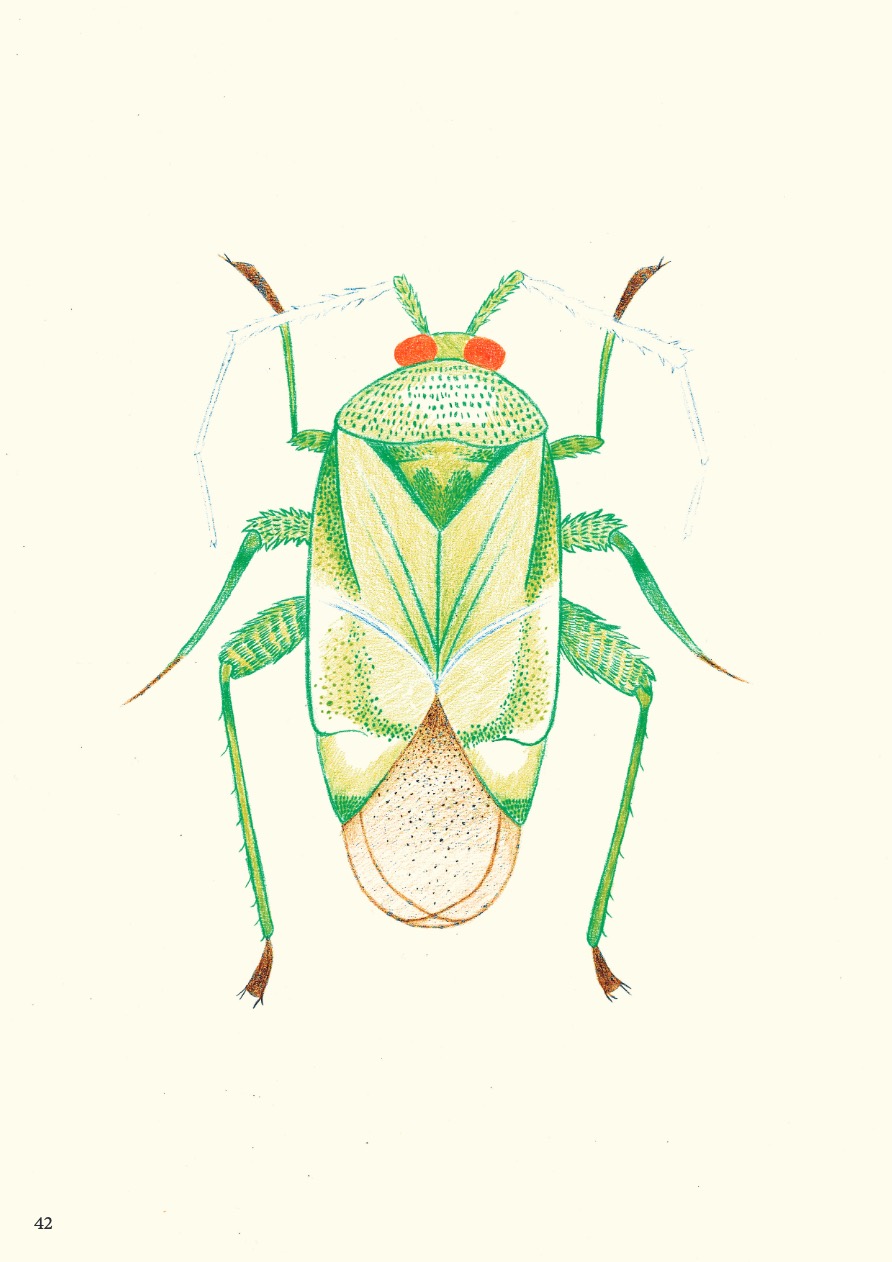

On the banks of the Sepik River in Papua New Guinea, the Iatmul people perpetuate a rite of passage based on their totemic animal: the crocodile. Many of their myths evoke the crocodile as the divinity of waters and the creator of the first submerged lands.

The ceremony begins with a procession through the village of around twenty men, walking in single file and symbolizing the ancestral crocodile. Adolescents are equal to women, so the main purpose of this initiation is to make them emerge from it as accomplished men, thus holding a superior status. For this to happen, the boys lie on small upturned canoes whose prows are sculpted with crocodile heads, while their back, thighs, chest and arms are scarified using a razor blade. During these operations, the boys aren’t allowed to show their pain. After the ceremony, the wounds are treated with medicinal plants, and these scarifications become very visible scars, representing a clear transformation of the boy’s body into a crocodile man.

From girl to woman

Kamayurá

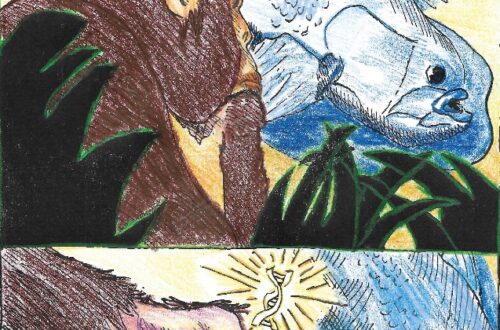

Kamayurá is an ethnic group living in the Mato Grosso region in Brazil. After getting their first period, young girls are confined in a part of the house and are strictly prohibited from leaving. During this period they learn how to perform domestic tasks, and they cannot cut their hair until their bangs cover their faces to chin level.

After a few months of seclusion, when the girls’ eyes are covered by the bangs, they can go outside to perform a dance. When dancing, no one is allowed to approach the young girl, nor look her in the eye. After that, she returns to her secluded area until her chin is also covered by her bangs. When leaving definitively, the girls’ bangs are cut and they are presented to the entire community as grown women, ready to be wives and mothers. Such seclusion seems to me like some sort of sacrifice or a penance, and reflects on a shameful aspect of becoming a woman, through the symbols of hair covering the girls’ faces, and people being prohibited to look at them.

Tchikumbi

@txt: In the Republic of Congo, Tchikumbi is known as an ancestral rite of initiation and fertility, marking the passage of the young girl from childhood to marriageable age. According to a myth, the sovereign of their kingdom, called Maloango, wanted to get married. He was then presented with a beautiful young girl who lacked all the virtues of a good wife. From that day on, the gods decreed that girls from the kingdom should follow an initiation rite to become suitable wifes.

The first menstruation marks the beginning of this rite. During a period of confinement which lasts from a few months to two years, a mistress and her companions teach the girl obligations that the community expects from her as a future woman, wife and mother. The girl is taught to do housework chores, basketry, and to have knowledge of myths. Today this ceremony has more of a symbolic value during customary weddings, for example highlighting the traditional attire worn by the bride.

Gender perspective

“We are not born a woman, we become one”, Simone de Beauvoir wrote in The Second Sex, 1949. From the moment we are born, there are things that are expected from us based on our gender. Through gestures, reflexes, feelings and visions of the world, we integrate these expected traits without realizing it. Traditional rites of passage reveal how becoming an adult isn’t the same experience according to one’s gender. Even among the most territorially distant societies, certain symbols and patterns often recur, because becoming a woman carries different responsibilities and expectations than becoming a man, and reflects sexist ideologies. Symbolically, becoming a man revolves a lot around unity, pain, but also respect and strength. Becoming a man means becoming a warrior, a wise being, a leader with a strong essence. Becoming a woman is portrayed quite differently, with the seclusion and isolation, to become not someone on your own, but someone for others. A wife, a mother.

The rites mentioned above are traditional and many don’t hold the same meaning as before. Still, it leaves us with the traces of how even something inevitable, such as becoming an adult, is heavily controlled and shaped by societal factors and by the patriarchy.